10/28/2024

Secrets of the Deep

Research Reveals Long-lasting Effects of the Oil Spill

Nearly 15 years ago, the oil drilling rig Deepwater Horizon exploded in the Gulf of Mexico. For nearly three months, an estimated 4 million barrels of oil spewed into the ocean. As a result of this environmental disaster, research has been underway across a multitude of disciplines for projects that span recovery and restoration to simply understanding the biological and ecological implications of releasing that amount of toxic material into an environment.

One such project, studying the effects of the disaster in the Gulf’s deepwater habitats, was recently renewed for an additional five years by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

Research contributing to the Deep Pelagic Nekton Dynamics of the Gulf of Mexico (DEEPEND | RESTORE) project has spanned 14 years and confirmed that the effects of the massive oil spill are apparent well below the surface – at least 1,500 meters down.

During the disaster, the focus of assessment and recovery efforts was on shallow and near-shore habitats like marshes.

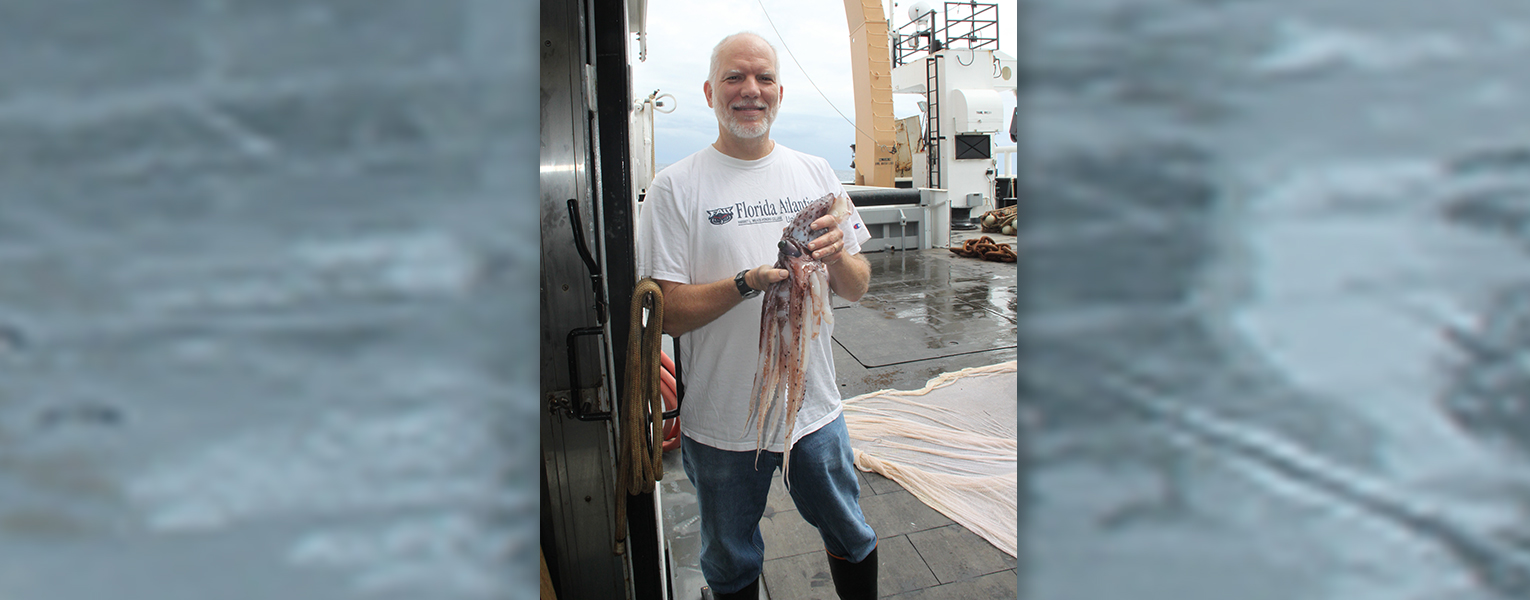

“NOAA’s natural resources damage assessment wasn’t immediately aware of issues in the deep sea,” said Jon Moore, Ph.D, a professor of biology in the Harriet L. Wilkes Honors College of Florida Atlantic University, a member of the research faculty at FAU Harbor Branch Oceanographic Institute, and a co-principal investigator on the DEEPEND | RESTORE project. “It was out of sight, out of mind.”

BP Exploration & Production, the operator of Deepwater Horizon, during the spill had used a chemical dispersant to emulsify oil and turn it into fine microdroplets.

“Some follow-up exploration found a river of oil droplets at 1,100 to 1,200 meters down that extended 250 miles towards Texas,” Moore said. “That’s when NOAA realized the scope of the impact on the deep sea.”

This September, NOAA granted $3.7 million for DEEPEND | RESTORE II to continue research, observation and monitoring of deep-sea pelagic species in the Gulf of Mexico. Florida Atlantic will receive $190,000 as a research partner. The longitudinal data have shown long-lasting negative effects from the oil spill, including petroleum-related toxins persisting in the tissue of organisms living thousands of feet below the surface. Due to the remote and delicate nature of these habitats, traditional restoration efforts aren’t feasible, but the long-term data collected during the study has unlocked new secrets of the deep.

“What we can do is monitor and inform our colleagues who have interests that relate to the deep sea,” Moore said. “Probably the largest animal migration on the planet occurs every day between the deep sea and the surface.”

During this nightly vertical migration, animals travel 400 to 500 meters up and down the water column, which means that the health and stability of deepwater habitats have a direct effect on near-surface ecosystems. Whales, sea turtles and sea birds, as well as prized gamefish like yellowfin tuna and swordfish all feed on these great migrators.

DEEPEND | RESTORE is a consortium of 47 researchers from 11 institutions across the United States. Moore was tapped to join the team in its earliest phase in 2010 for his expertise in taxonomy and the ecology of deep-sea animals. At that time, the project was called the Offshore Nekton Sampling and Analysis Program (ONSAP) and part of NOAA’s Natural Resource Damage Assessment. Moore and another co-investigator have identified 900 species of fishes captured during more than a decade of research cruises. They have found 15 to 20 potential new species to describe and created nearly 100 new records of species that were not known to reside in the Gulf of Mexico. Despite this species diversity, clear problems became apparent.

“The big take home is there is a huge loss of abundance,” Moore said. “There are some species that we haven’t seen since the project began. What the impacts of that absence on all those things that feed on them is hard to understand, and part of what we are trying to figure out in this new phase of DEEPEND.”

Members of the consortium have also received a new grant from NOAA for a project called Deep-Sea Benefits, which will complement DEEPEND’s extensive body of research by conducting a detailed examination of mesopelagic and deep-benthic (particularly deep coral) assemblages along the outer continental slope.

“With Deep-Sea Benefits, we will be monitoring interaction between deep-sea fishes and invertebrates that migrate toward the surface from as deep as 900 meters or more and a series of reef-like areas located along the continental slope,” Moore said.

In September, the team embarked on the project’s first research expedition focused on two deep-sea coral reef areas, the DeSoto Canyon and Viosca Knoll, located off Alabama’s Gulf Coast. Viosca Knoll, which is about 1,600 feet below the surface, is just 20 miles from the Deepwater Horizon site.

“These structures are biodiversity hotspots in the Gulf,” Moore said. “Our project aims to understand how these reefs are effectively benefiting from the deep-sea organisms that visit them every night.”

For more information, email dorcommunications@fau.edu to connect with the Research Communication team.

The principal investigator of the DEEPEND | RESTORE II: Trends and Drivers of the Pelagic Gulf of Mexico project is Tracey Sutton, Ph.D., a professor at the Department of Marine and Environmental Sciences, Halmos College of Arts and Sciences at Nova Southeastern University. The project is funded by NOAA’s National Center for Coastal Ocean Science.