While harmful algal blooms of red tide and blue-green algae receive a lot of press in South Florida, there’s another threat that’s emerged in recent years and choking the Caribbean — Sargassum seaweed.

Brian Lapointe, Ph.D., a research professor with FAU’s Harbor Branch Oceanographic Institute, has studied Sargassum seaweed since the 1980s. He’s long suspected that water quality issues, due to runoff and sewage, are the cause for the increasing Sargassum blooms. Now, in a recently published study, he’s confirmed that theory. Compared to the 1980s, Sargassum today has 35% more of the nutrient nitrogen in its tissues.

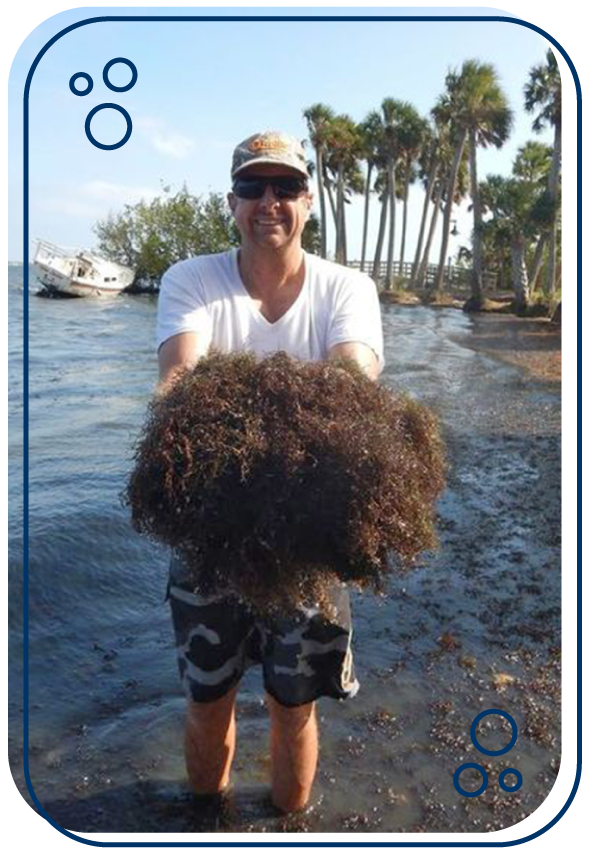

Sargassum seaweed is a type of floating brown algae. It drifts along the currents of the open ocean and accumulates in the Sargasso Sea, a region of the Atlantic Ocean bounded by four currents rather than land. Under normal circumstances, the seaweed provides shelter and food for an impressive array of marine life, like sea turtles, fish and crabs, as well as commercially important species like mahi-mahi, Lapointe said.

But more isn’t necessarily better, as is the case with Sargassum. With increasing nutrients from rivers including the Amazon and Orinoco in South America as well as the Mississippi, Sargassum becomes a problem. Since 2011, unprecedented strandings of the seaweed have occurred over vast areas of the North Atlantic basin and Caribbean. “It’s causing catastrophic problems in the Caribbean, because the massive amounts cause dead zones,” Lapointe said. “When it comes ashore, it’s just so much it strips the oxygen out of the water.”

The excessive Sargassum blooms are contributing to the decline of coral reefs, dangerous for wildlife by smothering sea turtle nesting sites or entangling dolphins surfacing to breathe, and even a threat to human health. When the rotting, foul-smelling seaweed clogs up canals and buries the beach, it releases hydrogen sulfide, which can irritate your eyes, nose and throat, according to the Florida Department of Health. It also contains heavy metals like arsenic and fecal bacteria. For that reason, the state monitors the water quality around beaches when Sargassum is present. You won’t catch Lapointe swimming at the beach during these times, he said.

For this study, Lapointe and his team collected a total of 488 samples of Sargassum between 1983 from 2019, from locations around the North Atlantic, including the Florida Keys, Gulf Stream, Sargasso Sea and reefs in Central and South America. The researchers analyzed the tissues and compared the baseline values in the 1980s to those in more recent decades. They found that nitrogen increased by 35%, while phosphorus decreased by 44%.

In Florida, and across the Caribbean, people are spending millions of dollars to mitigate this problem, which will likely get worse with global warming and the associated climate change, Lapointe said. With predictions including heavier rainfall and more severe storms, climate change has potential to release even more nutrients into the water, and further feeding the blooms.

The solution, Lapointe said, is to address our water quality issues locally, particularly due to septic tanks and sewage. “People talk about the fertilizer, but no one wants to talk about sewage. I’ve been fighting that for a long time in Florida,” he said. That’s slowly starting to change, however, despite being long overdue, Lapointe added. For instance, a recently approved senate bill, called the Clean Waterways Act, includes changes in wastewater treatment, reuse potable water and biosolids application.”

“The vitality of Florida’s environment, economy and way of life is dependent on the health of our waterbodies. That’s why the state prioritizes protecting and preserving Florida’s waterways by implementing sound, science-based solutions to current and future environmental challenges,” said Alexandra Kuchta, press secretary for the Florida Department of Environmental Protection (DEP). “The Clean Waterways Act is part of a multifaceted effort to improve and maintain the health of our waters for generations, and DEP looks forward to continuing working with partners to guarantee this success.”

Action to clean up our sewage to reduce nitrogen coming into the water is a start, Lapointe said. “If we want healthy oceans, we need to go on a nitrogen diet.” Emerging technologies are now available that can reduce nitrogen in sewage effluent by up to 98% and can be used anywhere without the need for a municipal collection system. Most importantly, they are as affordable as a conventional septic system, he said.

Lapointe is currently studying these systems with promising prognosis. “Our groundwater monitoring data for the On-Syte Performance system is showing a major reduction in nitrogen concentrations by this technology,” Lapointe said. “This could be a game changer for Florida and beyond.” ⬥